We are all affected by the scourge of mass incarceration, which harms people who are locked behind bars, their families and the communities they live in without making the public safer.

Many of the people in our prisons and jails, both those who have been convicted, and those who have been arrested but remain in jail because they cannot afford bail, have untreated or undiagnosed chronic illnesses, behavioral and mental health challenges and substance use disorders. They often live in communities that have been harmed by structural racism and that are overpoliced, leading to a far larger share of Black and brown people who end up in prison or jail.

Incarceration, even for a short time, increases the struggles many people already face, including finding affordable housing, transportation and a job that pays enough to support a family, making it more difficult than it already was to meet basic needs.

And the harms spread well beyond incarcerated people to their children, families and broader communities, ripping them apart and making them less stable.

Incarceration doesn’t make Kentucky communities safer

- Research consistently shows increased incarceration doesn’t result in lower rates of violent crime or help those with substance use disorders.

- Even for serious crimes involving interpersonal violence, simply adding more criminal laws does not serve as prevention or otherwise address systemic and root causes of violence.

Incarceration doesn’t solve community problems

- Incarcerating more people for selling drugs does not reduce the supply of drugs or make communities safer. Despite Kentucky’s incarceration trends, the state was fourth in the nation in drug overdose deaths in 2021.

- Many of the behaviors criminal legislation attempts to address, such as gun violence, domestic and partner violence, and child abuse and neglect, are symptomatic of deeper issues including poverty, cyclical trauma, lack of gun regulations, mental health disorders and substance use.

- In addition to being harmful and unjust, incarceration doesn’t make sense as an economic development strategy. Building prisons in rural Kentucky has not significantly improved poverty rates or employment and country-level investments in expanding jails result in significant debt while relying on rising levels of incarceration. Kentucky counties that invest in expanding local jails in order to have the state cover more of their costs end up locked into significant and risky amounts of debt that depend on maintaining or increasing high levels of incarceration.

Incarceration reduces quality of life, harms health and well-being

- Being incarcerated correlates with poor health outcomes and reduced life expectancy, regardless of sentence length, and people who are incarcerated experience greater financial instability and hardship, poorer mental health and higher rates of substance use and overdosing.

- Formerly incarcerated people also face “second-class citizenship” from having a criminal record, which leads to issues obtaining housing, employment and other social needs.

Incarceration can actually make communities less safe

- When incarceration increases, states with high incarceration rates can actually see an increase in crime.

- Incarceration for even a short amount of time has collateral consequences, including employment and housing loss.

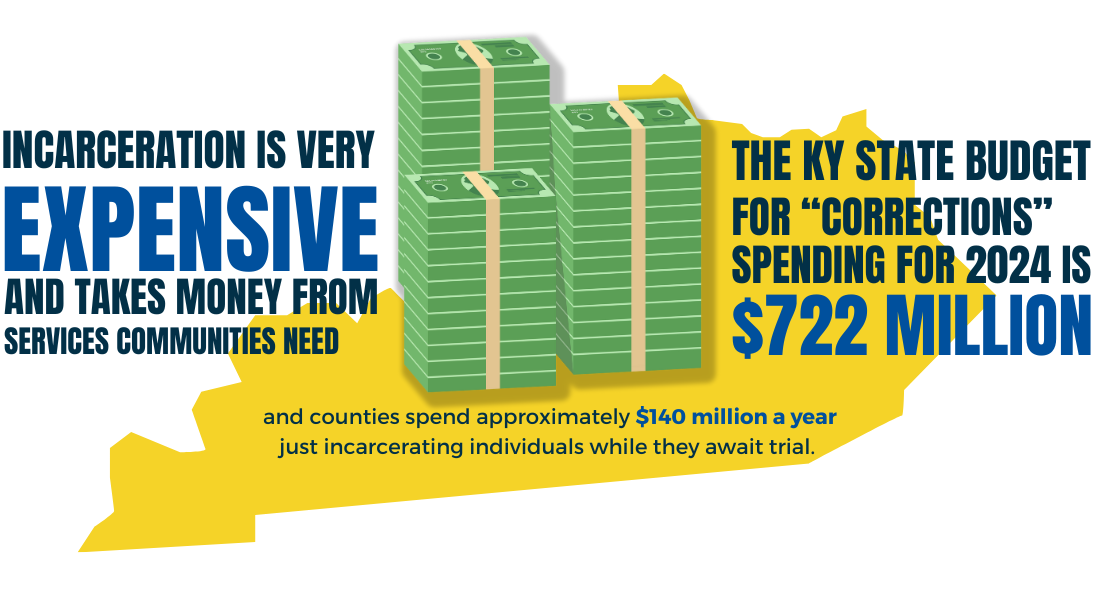

- The money communities spend on incarceration means fewer resources to invest in mental health supports and substance use disorder treatment, among other critical investments that would improve public safety in truly meaningful ways.